The Good Neighbour

The Good Neighbour

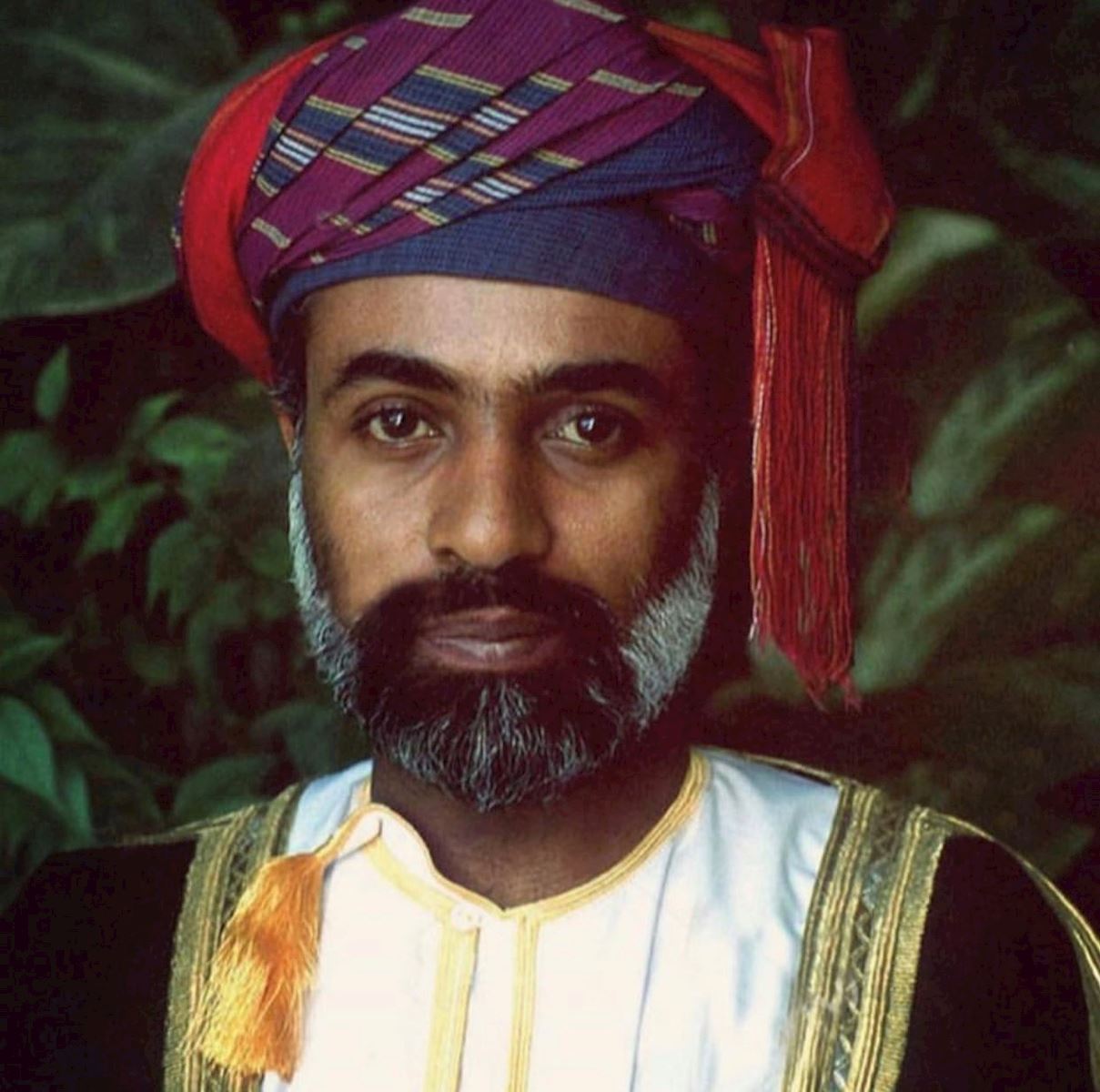

A Commemorative Lecture on the Life of Sultan Qaboos

April 2nd 2020

My thanks to the Anglo Omani Society for inviting me to give this lecture, especially to the chair Stuart Laing.

My thanks to you for listening.

I have been visiting Oman for nearly forty years. As for most Omanis, His late Majesty Sultan Qaboos and Oman have been, for me, more or less synonymous. This is a measure of just how significant has been his influence on the very character and tone of Omani public and social life.

Although I only had the privilege of meeting His late Majesty on one single – and memorable – occasion, every time I am in the country, I am conscious of his influence. Calmness, hospitality, courtesy and unfailing generosity with time and energy: these are some of the characteristics of the Omanis with whom I have interacted over the years. Characteristics that are no doubt deeply familiar to all of you. These are, of course, the personal attributes of different individuals around the country. But their persistence and pervasiveness owe much to the personal example of Sultan Qaboos. As we remember him, we continue to live in the presence of his particular genius for social grace, manifest in the public life of the citizens who embody his ethics. These attributes provide an important foundation as Oman moves forward under His Majesty Sultan Haitham.

I would like to share some ideas about the most important contributions made by Sultan Qaboos to the life of Oman. There have been very few, if any, world leaders whose individual contribution, through public service, have been so

intimately and inextricably linked with the development of their country, and who have been held, at home and abroad, in such extraordinary esteem. While I cannot begin to do justice to the scope and scale of what Sultan Qaboos achieved during his nearly fifty years leading Oman, I can at least attempt to illuminate a few distinctive features of that achievement, in those areas of Omani life and public policy with which I am familiar.

1.

There are four areas in particular, which deserve attention:

- The first is foreign policy, where Oman's independence and commitment to conflict resolution is directly attributable to the guidance of Sultan Qaboos, and which has been widely recognised, both during his lifetime and following his death, in assessments of his regional and global significance;

- The second is political development; where in the 1990s, in particular, Sultan Qaboos set in motion the development of institutions through which Omani citizens have the opportunity, created for them by His late Majesty, to participate in shaping their political future;

- A third area is social policy, especially in the area of health, where Sultan Qaboos's faith in Omani social solidarity permitted some remarkable advances in primary care, recognised by global authorities as unusually rapid and responsive. Achievements public education have also been remarkable.

- Finally, I want to talk a little about Omani culture, where Sultan Qaboos's commitment to and advocacy of Islam's open and tolerant character, drawing in particular on the Ibadi traditions of shura and ijtihad, has been consistent at a time when narrow and dangerous voices have tried to dominate the discourse.

Through each of these four areas, there is a thread of continuity. A theme, if you like, that tells us something about Sultan Qaboos, as a man and as a leader. This is where the title of this lecture comes from. For in each of the four areas I am going to discuss, Sultan Qaboos, I suggest, made sure that Oman could always be relied upon to be the Good Neighbour.

So first let us consider what it means to be a good neighbour. At this strange and difficult time, as we all reorganise our everyday lives in the face of the pandemic, the question of what it means to be a good neighbour has no doubt been very much in our minds. The Good Neighbour, I suggest:

- is always there, and available for conversation,

- but is also sensitive to your desire for peace and quiet,

- is on hand to offer practical support but is not intrusive,

- shares responsibility for looking after the neighbourhood and the wellbeing of everyone in it,

- recognises that cooperation and consultation among neighbours is the best way to find solutions to shared problems and to build a better neighbourhood for the future.

Now let us consider the four specific areas in which Sultan Qaboos acted as a good neighbour.

2.

Oman's foreign policy is an area which His Majesty Sultan Haitham emphasised in his inaugural speech, and it is probably the aspect of Sultan Qaboos's rule that attracted both the most and the most favourable comment in the media at the time of his death. Commentary tended to focus primarily – and understandably – on the tangible and practical ways that Oman has assisted its friends and allies in dealing with intractable problems and disputes. The image of a country practising skillful diplomacy behind the scenes is an attractive one, and vividly captures and communicates something of the policy reality. But there is more to this than behind the scenes diplomatic interventions. Such interventions were only possible because under Sultan Qaboos, Oman had established a foreign policy position that was understood by its friends and neighbours and that established the conditions of trust under which such interventions could be made. It is the long and sustained commitment to this policy for which Sultan Qaboos really deserves significant credit, and which is worthy of some closer examination.

Sultan Qaboos came to the throne when Oman faced challenges that could very easily have encouraged a defensive and even hostile attitude towards immediate neighbours. Its largest and most powerful neighbour on the Arabian Peninsula – Saudi Arabia – had actively supported armed opponents of the Sultanate within recent memory and was still far from clear in its recognition of Omani sovereignty. The Trucial States, soon to join in federation as the United Arab Emirates, also queried the legitimacy and integrity of Oman's borders. Above all, of course, the government of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen was actively supporting the insurrection in Dhofar that posed an existential challenge to the Sultanate of Oman.

Rather than responding negatively to this situation, Sultan Qaboos instead acted very swiftly upon his accession to the throne to build important relationships with key neighbours, which as I am sure you'll all recall, led to some vital Omani cooperation with both Iran and Jordan (as well, as, of course, with the UK) to counteract and bring to an end the Dhofar insurgency. It also allowed a process of reconciliation and national renewal, in which neighbours who had once been at war with one another within Oman itself, were able to start working together, at every level, from local communities to central government ministries.

At the same time, Sultan Qaboos took action to ensure that Oman's relations with the international community more generally were established on an appropriate footing. He did so against a certain amount of regional opposition, some of which even questioned the legitimacy of his rule and the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Oman. Oman's efforts in this regard, in which Sultan Haitham’s father, Sayyid Tariq, of course, played a significant role, were successful in gaining international recognition and inaugurating Oman's participation in key international and regional organisations, such as the United Nations and the Arab League. Oman was therefore able to make sure of its own position in its immediate neighbourhood, moving towards border agreements with all its neighbours, agreements which were then the basis for enhanced cross-border, or shall we say, neighbourly cooperation.

Sultan Qaboos himself devoted considerable time and personal energy to this cause, and in the course of these early years of his reign successfully established strong and valuable personal relationships with key neighbours, initiated by making high profile visits to meet each of them in person. These personal relationships with leaders in the neighbourhood, especially those with Shaikh

Zayed of Abu Dhabi and King Hussein of Jordan, would prove vital to Oman's development of a distinctive, pragmatic and moderate foreign policy.

In other words, a great deal of the work of securing Oman's security, stability and long term independence during the early years of Sultan Qaboos's reign was devoted to making sure that Oman's relationships with its neighbours were established on secure foundations. Under him Oman made it very clear that it sought fruitful and cooperative relationships with all its neighbours, and welcomed their cooperation and support. This approach also signaled the crucial quid pro quo, that Oman would stand ready to offer support, assistance and cooperation, to all its neighbours, whenever needed.

So, these were the key foundations for the new Sultanate of Oman that he was seeking to lead into existence. It is quite striking, I think, that Sultan Qaboos laid them so early in his reign. In the acute circumstances of 1970 he appears rapidly to have concluded that good relationships with neighbours – of all kinds – are essential if you want independence and to build a good life for those you lead.

The core principles of Omani foreign policy as it is now understood really came into focus in the 1990s. It was the result of a series of historical experiences of great significance for Oman: first the Iranian revolution of 1979, then the IranIraq war of the 1980s, and finally the end of the Cold War.

Experiences of upheaval and conflict in the Gulf required that the leader of a small nation, living in close proximity to two larger states who were at war with one another, and facing pressure to choose sides by other neighbours, should develop a policy in which the national interest could be preserved by maintaining good relations with all parties. The acute nature of the successive

regional crises also prompted a desire to do something to mitigate its effects. Keeping channels of communication open with all parties may have begun as a means of self-preservation, but it developed into a recognition that this stance would enable a more active engagement, of the kind that would eventually lead to the facilitating diplomacy for which Sultan Qaboos would later become celebrated.

The end of the Cold War hastened this consolidation into a clear policy. Sultan Qaboos was unusually quick to grasp the magnitude of the change that the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe would begin. He was certainly commissioning detailed analysis on these events and their ramifications very early on. I think he recognised that the post Cold War situation would undo the logic according to which everyone had to take sides, and that it would require a much more nimble foreign policy to engage adequately with a multi-polar world.

It is in response to these experiences, then, that core foreign policy principles, directly attributable to Sultan Qaboos's understanding of Oman's particular geopolitical situation, were developed and established. The core principles are, first, that no relationship, interaction or negotiation should be considered as a zerosum game. Second, regional security in the Middle East can only be effective if all the key players and interests in the region cooperate with each other, rather than organising against one another. It needs to be collective. Third, all channels of communication should be kept open: boycotts, refusals to cooperate, severing diplomatic relations all run counter to the aim of being a good neighbour.

Once these core principles had been established – and, indeed, started to be articulated quite explicitly by Omani government officials – Sultan Qaboos,

who had developed them, through his own diplomatic practice, even if he never theorised about them, never departed from them, even under circumstances in which the pressure to do so must have been intense.

Building on the work of J.C.Wilkinson it is not entirely fanciful, I think, to consider Oman's approach to foreign policy as the manifestation, in an international context, of a habit of thought shaped by a centuries-long culture of local water-sharing. In other words, its core principles derive from a particular understanding of a neighbourhood, as a place and a set of relations that depend upon high levels of cooperation and a sense of self-interest that is not set against the interests of others. Water from an Omani falaj has to be shared out in a cooperative way, which is agreed upon according to long-established practice, and respected as though it were encoded in law. The advantages of this kind of cooperation are self-evident to such an extent that it would not make sense for anyone to propose an alternative in which individuals pursue their own advantage, at the expense of their neighbours.

This approach to regional politics and cooperation was behind Sultan Qaboos's leadership of Oman's participation in the Middle East Peace Process from 1991. Clearly the policy of maintaining all channels of communication has already been articulated and acted upon, as early as Sultan Qaboos's startlingly bold decision in 1979 not to join the Arab League boycott of Egypt over its peace agreement with Israel. It was entirely in keeping with this position that Oman joined the Madrid process in 1991 and worked actively in a multilateral context to promote a peace settlement. That Oman did so primarily by means of the Water Resources Working Group and the foundation of the Middle East Desalination Research Centre will have come as no surprise to anyone who had grasped the connection between Oman's foreign policy and its people's experience with the collective management of water supplies. By engaging in

this way Sultan Qaboos could lead Oman into the careful exploration of dialogue with Israel, including the visit to Muscat by Prime Minister Rabin in December 1994. That Oman sent a high level delegation, led by Yusuf bin Alawi, to Rabin's funeral the following year is a further indication of the value Sultan Qaboos consistently placed on the idea of conducting foreign policy as a good neighbour.

In foreign policy, the good neighbour is the one who places the wellbeing of the neighbourhood above individual or national interest. Or rather, recognises that the national interest is in fact best served by attending to the interests of the neighbourhood. The good neighbour is the one who is prepared to talk to all other neighbours, and to seek collective solutions rather than outcomes that favour one party at the expense of another.

It is fairly clear how Sultan Qaboos acted as the good neighbour in foreign policy, and he richly deserves the credit he has received for doing so. But I think it's important to understand how he applied the same principle across other, perhaps less obvious, domains. Including, first of all, Oman's political development.

3.

Oman's political development has not been widely discussed for some time. Sultan Qaboos's contribution to it – by which I refer mainly to the process by which more effective and more representative Omani institutions evolved – has not received the attention it deserves. In the mid 1990s he made a number of initiatives, which were not only significant at the time, but which, I believe, also

hold great potential for Oman's future. Taken together, these initiatives could turn out to be one of the most enduring elements of his legacy.

They were an important part of his nation-building project, which consistently involved gestures of political inclusion: from the reconciliation with former opponents of his father’s rule, through the incorporation into government of talented individuals from diverse cultural and geographic backgrounds, to the appointment of women to serve in the cabinet from 2004.

The first of the vital initiative of the 1990s was the gradual opening up of Majlis ash-Shura to universal adult suffrage. The second was the establishment of Majlis ad'Dowla. The third, which was essential for the consolidation of the development of both Majlis ash-Shura and Majlis ad'Dowla, was the promulgation of the Basic Law in 1996. These developments received a fair amount of attention at the time: for example the election of the first women to Majlis ash-Shura in 1994 was widely commented upon, in the context of reporting of Sultan Qaboos's repeated calls for women to be able to play their full role in the project of national development.

But overall, the process of Oman's political development is one which mainstream commentary has since done surprisingly little to illuminate. It was something of a shock to notice, for example, that, shortly before Sultan Qaboos's death was announced, speculation about the succession in The Guardian – a newspaper one might expect to know better – described the plans for the succession as 'baroque'.

As we all know, these supposedly 'baroque' arrangements were outlined in Oman's Basic Law of 1996, and, involve a process of consultation among a clearly identified group, and are underpinned by written instructions. This is

hardly complex or exotic, yet the term 'baroque' suggests something that is both unnecessarily elaborate as well as anachronistic.

Leaving aside for another time the critique I might want to offer of the orientalism of this choice of language, what matters here is that developments in the mid-1990s, initiated and led by Sultan Qaboos, have in fact laid foundations upon which a number of possible developments and new institutions could appear in the future.

Qaboos’s 1996 Basic Law built on the understanding developed over the previous twenty-five years that the ruling family, the executive, the judiciary and the parliament were interdependent elements in the structure of power and responsibility, with the Sultan himself at the pinnacle. The Basic Law also took full account of the longstanding traditions of shura (or consultation) that have traditionally characterised life in Oman, not just political life. But to these elements Qaboos subtly introduced a new dynamic. This created a direction of travel for the institutions of the State towards what could in the future be much fuller participation by Oman’s citizens in the country’s governance. In short, Qaboos offered a framework which created possibilities for others to take up, but without stipulating how to make use of these opportunities.

For example, contrary to what is routinely asserted by many commentators the Basic Law does not forbid political parties. In fact in Article 33, it rather quietly creates the constitutional basis for their formation, I quote:

“The freedom of forming societies on a national basis, for legitimate objectives, by peaceful means, and in a manner that does not conflict with the provisions and objectives of this Basic Statute, is guaranteed in accordance with the terms and conditions prescribed by the Law”.

Sultan Qaboos moved this process a bit further in his only later amendment to the Basic Law; significantly this followed the popular demonstrations of 2011. Here he deliberately enhanced the powers and role of the parliament to include among other things the participation of the leaders of both houses in the succession process. It was significant that the provisions of the Basic Law, including this element, were followed to the letter this January in the transition from Sultan Qaboos to Sultan Haitham, and that it was all done totally transparently in the full public gaze.

Those of you who saw the television broadcast of the meeting between the Family Council and the Defence Council will have noted that once the Family Council had decided that they should ask for Qaboos’s letter to be opened, officials took responsibility for the process which was then carried through in front of the cameras. We saw that it was the acting chair of the Defence Council, the Minister of the Royal Office, who opened the first envelope, and the Minister of the Diwan who opened the second. The Family Council sat and listened, as witnesses to the process. The non-family representatives of government together with the Chairman of Majlis ad-Dowla, the Chairman of Majlis ash-Shura, and members of the Supreme Court were present both as witnesses and as the voices through which Sultan Qaboos communicated his choice of successor to his own family and indeed to all Omani citizens. There was no private family decision on the succession.

It has been nearly twenty five years since Sultan Qaboos promulgated the Basic Law. I suspect that when we look back in another twenty five years, those of us who are still here will be able to see, far more clearly than people do now, that his strategic openness to what others might decide and be able to do, was one of his most substantial contributions to the future of the country. It will also be

clear, I think, that Sultan Qaboos's own role in Oman's modern history – with his formal control of all the key levers of government – made his reign sui generis. This is a rather paradoxical legacy, perhaps, but typical, I think, of Sultan Qaboos, in its modesty and its willingness to make allowance both for the contingency of history and for the decisions and preferences of others.

The Good Neighbour recognises, in other words, that he does not have a monopoly on wisdom and expertise, and that the same principles of consultation that make for a harmonious and forward-looking neighbourhood also make for sound domestic politics.

4.

Before I move towards a conclusion, by talking about the culture that His Majesty Sultan Qaboos fostered in Oman, I want to take a moment briefly to highlight another dimension of what a domestic policy that attends to the idea of being a good neighbour can achieve. Oman is by no means alone among its neighbours in having made good use of its revenues from oil and gas to provide citizens with high quality education and welfare. There has been great achievement across a range of social policy, from the construction of infrastructure (electricity, water, roads) to the development of public education. In 2010 the United Nations Development Report studied human development for every country in the world over the 40 year time frame 1970 to 2010 and ranked Oman first. China was second. This is a remarkable fact and that it is not well known speaks volumes about Omani grace and modesty. But as a series of surveys and assessments from the World Health Organisation have shown, Oman under Sultan Qaboos was particularly successful in the field of health. Oman's focus on localised primary health care built effectively on the same longstanding values of social solidarity that characterise falaj usage, and

encouraged the delivery of services at the neighbourhood level. This led to some quite remarkable achievements, including an immunisation programme which brought about one of the most rapid declines in infant mortality ever recorded, as well as the highest global ranking, first among 191 member countries, for the efficiency with which the Omani system translated expenditure into health outcomes, according to the World Health Report of the year 2000.

These achievements are not only consistent with Sultan Qaboos's approach to foreign policy and political development which I have already described. They are also a result of thinking about what it means to be a good neighbour, and developing government policy in such a way as to encourage citizens to act in solidarity with one another. By making health care a matter of local concern, supported collectively, rather than a remote, top-down provision or a marketplace, Sultan Qaboos not only made sure that the health of Omani citizens was taken care of, but he also promoted an ethos of good neighbourliness at a time when the pressures of rapid social and economic change could so easily have undermined it. As Oman responds to the global coronavirus pandemic, this ethos and the public health system that embodies it seem to be proving their worth.

5.

This brings me to my final point. Clearly the last 50 years have been a period of extraordinary transformation for Oman. Sultan Qaboos will always be remembered for having made this possible, and for having led his country through this historic process of social, economic and political change.

But he will also be remembered for having preserved so much, particularly in the field of culture. By this I don't mean simply the preservation of traditional arts and music, nor even the investment in new cultural institutions like the Royal Opera House. I am talking about something much broader: about culture as a particular way of life, which expresses certain meanings and values not only in art and learning but also in institutions and indeed, and above all, in ordinary behaviour.

What Sultan Qaboos achieved – and in this I think he has set a quite remarkable example – was to encourage the continuity of a distinctively Omani culture. It is this continuity that makes Oman feel unique today. It is the source of the grace that still pervades everyday social interactions. It has not involved a refusal to move with the times, or to adapt and take up the best of what modern life has to offer, but it has entailed an insistence on keeping hold of some older ways of doing things that are of particular value. This has come, at least in part, from Sultan Qaboos's attention to some of Islam's essential teachings, which urge precisely the kind of social solidarity, good-neighbourliness and tolerance for the beliefs of others that I have described as animating his approach to policy on multiple fronts.

As long ago as 1994 he spoke out clearly in that year’s National Day speech against the dangerous certainties that motivate extremists. He insisted that Islam calls not only for intellectual development drawing on the teachings of the past but also for productive engagement with western societies. This was a bold statement at a time when the danger of such extremism was much less understood than today.

This approach is an extraordinarily precious thing. It will underpin the country under the new leadership of Sultan Haitham. The persistence of such a culture makes a society strong and resilient. It allows people to be open, generous and tolerant. Sultan Qaboos – the Good Neighbour who was also, in his quiet and understated way, a great leader – embodied this culture. For everyone who loves Oman, this marks the scale of our loss. But it also explains our optimism for the future.

Thank you.