His Quest for the Lost City of Ubar and Other Omani Adventures

Sir Ranulph Fiennes

23 June 2020

This podcast has been edited for publication. Any mistakes or discrepancies with the original podcast are the fault of the Editor alone.

.jpg)

Sarika Breeze Described by The Guinness Book of World Records as “the world’s greatest living explorer”, Sir Ranulph Fiennes has led myriad expeditions, including completing seven marathons in seven continents in seven consecutive days, hover-crafting over the length of the Nile, and leading the only expedition to have ever travelled around the world, including both poles, vertically.

His experience in Oman started when he was seconded to the Sultan’s Armed Forces in the 60s, and continued through the next decades as he searched for, and eventually found, Arabia’s lost city of Ubar, also known as Atlantis of the Sands. His experience in Oman has even played a role in his recently-launched rum, named Sir Ranulph Fiennes’ Great British Rum, which uses Omani date palms as one of the wood flavourings. Sir Ran was awarded the Sultan’s Bravery Medal in 1970 and was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1993, having raised millions of pounds for worthy causes through his expeditions. Without further ado, I give you Sir Ranulph Fiennes…

Thank you very much for joining me today. It's great to have you on with us. First, could you please tell us a little bit about what initially brought you to Oman?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes I was getting fed up in the mid-sixties with confronting the Soviet Union. At that time, the Brits expected the possibility that the Soviet Armed Forces in Eastern Europe (which was called the Warsaw Pact) were likely to attack and the defences by the Americans and the British and the French all along the border between West Germany and East Germany, including a lot of European Union, the United Nations tanks. At the time I was a second lieutenant, the lowest form of officer. I had three 70 tonne tanks – that was part of the defence on the border with the regiment called the Royal Scots Greys. Greys as opposed to Blacks. My father had commanded that regiment when he was killed in 1943, four months before I was born. All my young life, having heard stories from my mum about my father, I wanted to be what he had been, which was commanding officer of that tank/cavalry regiment.

But my first 11 years, from the age of one, we lived with my South African granny (my father's mother). When my father was killed – and his elder brother had been killed in the first world war in the Gordon Highlanders – so both her sons by my English grandfather had been killed. My English grandfather died of old age and so my South African granny, in her eighties, wanted to die back where she came from near Cape Town. She took us in as it were – my mum, three elder sisters and me. Our first 11 years until granny died were in South Africa and when she did die, mum brought us all back to England. But I didn’t really know England, it didn't really mean much apart from the fact it was called England. My education had been four schools in South Africa and not to the same sort of standard as what they call A Levels. To get into a situation in the British army at that time you needed to go to Sandhurst College, then you come out and get the regular officer commission, but to get into Sandhurst you needed A Levels and I just couldn't get them.

So I took the other thing, which was called Mons Cadet School. However, that only gets you a short-service three-year officer commission and you are less likely to reach the top of the regiment and be the colonel than people who had passed Sandhurst. So there we go. Eventually, after doing Mons and a three year commission, you were then allowed to sign on for a year at a time five times. That was your lot.

So after eight years, I knew that I would be not reaching Colonel of the Scots Greys, therefore in Germany, as I say, for three years in the early sixties with the tanks, I thought ‘well, if I'm going to sign on, I’ll sign on to something where we actually see some action against the Soviet Union!’ Because in ‘67 the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, removed the Brits from Yemen, or rather Aden, South Yemen, and the Soviets moved in there and started attacking the next door country of Oman over the Yemeni border.

The Brits had a 300-year treaty with the Sultans of Oman, so when the Omanis asked for their help, they sent out volunteer officers. All the troops, all the actual people on the ground, were volunteer Omanis or from across the Gulf, Baluchi mercenaries and a few Omani Zanzibaris. We had a mixed bunch of soldiers. I went out there and, because I'd been with tanks, the Muscat regiment decided to put me with the nearest thing: Land Rovers! A Reconnaissance Platoon of six open Land Rovers with machine guns.

We were told to do two things: stop the incoming Soviet weapons over the border from the Yemen, and then also those coming either along the coastal route, which was mountains and heavy vegetation right down to the Indian Ocean coast. They could go that way to come into Oman with all their weapons.

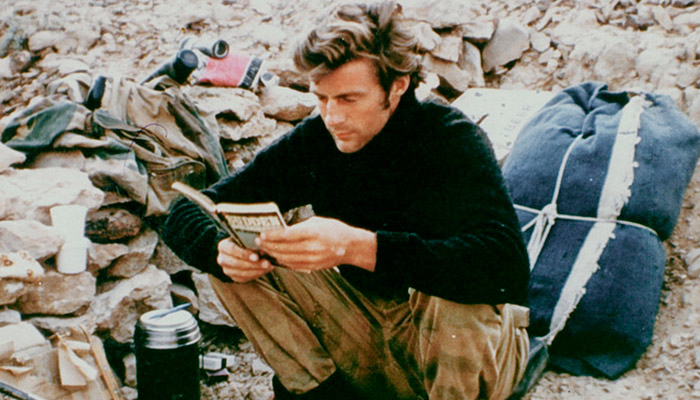

There were about 2000 of them, very well trained and armed in the Soviet Union, mostly in those days in the Ukraine and sent back better armed than the Sultan’s soldiers, our lot. And 2000 of them. Now, when I arrived there in ‘68, there were about 190 soldiers armed and active in the mountains or in the desert to the north of the mountains, which stretches all the way out to Saudi Arabia. So when our Land Rovers couldn't go – literally – because of sand dunes to the North (well, we went in there, but with difficulty), or into the mountains, which went up high from desert to jungle type stuff, we would park Land Rovers in the semi-safety of the desert, wait ‘til night, because the SAS – I forgot to mention, I’d been in the SAS in between leaving the tank regiment and joining the Sultan’s Forces.

So, I'd been in the SAS, I’d passed the selection and jungle training, but I misbehaved using army explosives to blow up civilian property in England in Wiltshire.

Sarika Breeze Tell us a bit more about that?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Well, there was a village in Wiltshire, near Chippenham, called Castle Combe. It had been voted Britain’s prettiest village and some of my friends from school days had become wine salesman in the West country. They heard from the villagers in Castle Combe that it was not popular that 20th Century Fox were making the beautiful village as the backdrop for Doctor Dolittle with Rex Harrison and people. They objected to the fact that the lovely trout stream had been dammed up with a concrete dam to make a lake for filming on. They said we ought to object on behalf of the villagers. So, it got in the press that the villagers didn't like it. When 20th Century Fox left, they wanted someone to remove all these concrete things. So they asked me, because they knew I had explosives to help out, but somebody told the police. Then the police were waiting that night and all our group except me were caught, but they had the car numbers including my car.

So I ended up heavily fined and with six months’ probation in Salisbury to the police and sent from my regiment to a holding regiment. They would throw me out of the army if we were put in prison, luckily the judge fined us instead, all four of us. The papers called us the Three Just Men. And so I did get back to my tank regiment, the Scots Greys, my dad's regiment, after six months away and then it was back to the same tanks, the same waiting the Soviets. And that's why I applied to the Sultan’s Forces.

But going back to fighting in the desert, we would, as I say, park the Land Rovers, and after night we would move into the mountains and lay ambush on the information of the intelligence officer, Tim Landon. He was a wonderful guy. For two years, we did this ambush stuff, but we were heavily, heavily outnumbered. We had to be very stealthy indeed. We learned to move in enemy territory and ambush the political commissars who were raping villagers’ daughters and so on. Then a price was put on the head of our unit. Yes, it was exciting times. I wrote a book about it which you can get from Amazon called Where Soldiers Fear to Tread in which I put all our experiences at that time with photographs.

Sarika Breeze And was it during your time in the Sultan’s Armed Forces that you first heard of the Lost City of Ubar?

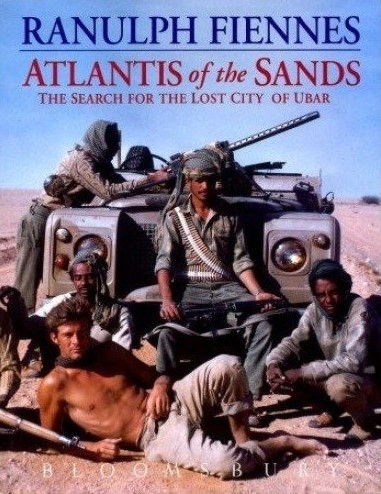

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Yes, it was. I've got a photograph of me in front of a Land Rover in the desert with my particular group of four. In that photograph, there's a guy just sitting next to me with a gun who was called Sheikh Nashran bin Sultan. He was from a Bedu tribe and we got a lot of information from the Bedouins against the Communists out in the desert.

One day, after over a year working with Nashran, we were having coffee in the desert, and he said ‘the tracks that we passed yesterday in the neighbourhood of Shisr, they go to the Lost City of Frankincense. To get the frankincense to Jerusalem, 900 miles without water, there would be 25 camels to one man, and they would each carry two sacks of frankincense’. And when we weren't blocking the Communists, every now and again – it was quite naughty I suppose – but we would divert a couple of Land Rovers to look for the Lost City, leaving four to block the arms’ incoming routes.

They use personnel mines against our lot. We had an Australian captain in our headquarters company, a wonderful guy called Spike, who had fought in Rhodesia years before and he knew about Soviet weapons. When we were being threatened with the personnel mines, which would blow your leg off, he said ‘well, we'd better mine them on the infiltration routes!’ and he made mines out of Coca-Cola tins, using small batteries and detonating pins. We were instructed to leave them on all known infiltration routes. I was sent out to lay the mines and a two and a half years later, when my time was up with Oman, I went out and removed them all again, which is quite hazardous.

Sarika Breeze And then when your job in Oman was completed, you found yourself going back to search for the Lost City of Ubar?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Exactly.

Sarika Breeze So, other than the fact that it was important in the frankincense trade, what did you know about it at that point?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Marco Polo had mentioned it and there were all sorts of Bedu that we ran into and got information from over those two years, and they all confirmed that it was there. There was a guy called Wendell Phillips who for a bit had been friendly with our boss, the Sultan of Oman, Said bin Taimur, the father of Qaboos.

You probably know that Qaboos was brought up in the UK, went to Sandhurst, became a captain in the Cameronian, until they got stopped by the government when the army was being made smaller. He then went back to Oman in his mid-twenties, probably. Qaboos went back and his father, Said, my boss, put him not under house arrest, but captive in a lovely part of the palace in Salalah. Lots of times I had to report to Sultan Said bin Taimur in order to do things like protecting the Sultan’s waterhole.

I liked him very much, good old Said bin Taimur. He didn't have much money at all so he couldn't build roads or hospitals or schools, and that made it easy at that time for the Soviet Union propaganda to turn people against my boss and say he was very reactionary. Which you could say he was, but, you know, where did the money come from? Because oil had not been found.

Anyway, what I didn't know was that my friend, the intelligence officer Tim Landon, was in secret talks with the British prime minister, who realised that this reactionary situation would have to stop and that if they put this young son, Qaboos, into the Sultanate as the new Sultan, it would help. However, that would mean removing Said, my boss. So, whilst Tim was telling me what to do, and I really liked Tim, I didn't realise that he was planning to get rid of my boss. And the only reason he could do that was because he was a good friend at Sandhurst of Qaboos. So Said thought ‘well, although I'm keeping Qaboos in the palace, learning the Quran et cetera, I will not let him not speak to possible conspiratorial locals, but I will let him speak to his old English friends, we can trust them’. Ha ha.

So Tim and Qaboos plotted it together. About a month after my time was up in Oman, I think we're talking June or July ’70, I heard that my regiment had been involved with other Muscat regiments in a palace coup. Qaboos was now the boss. My boss had been, what do you call it? Evicted and was put up in a top wing of the Dorchester in London, together with his wives and some servants. After he’d been there 18 months, I was involved with getting a visit from Qaboos to his dad. They were quite good friends by then again, because Said did like the Dorchester and Qaboos was getting on very well because oil revenue was coming in.

Sarika Breeze Did you feel at the time that it was a good thing that His Majesty Sultan Qaboos was coming to power?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Yeah, after a bit. Qaboos was in London and I remember – I forget the name of it, it was like #2 Park Lane right next to Hyde Park corner. It was a very posh restaurant. I remember meeting him there and telling him that I had become an expedition person, but I needed sponsorship for Antarctica and that if His Majesty very kindly organised sponsorship, I would get photographs of the Sultan of Oman’s flag at the South Pole.

Through his very good friend, Dr Omar Zawawi, we were sponsored by Tarmac who wanted business at building roads in Oman. So we got the money and I flew the flag at the South Pole on one of our expeditions and, on another, we called it the Jebel Shams Expedition. Again, on our Polar Global, we put up the Omani flag.

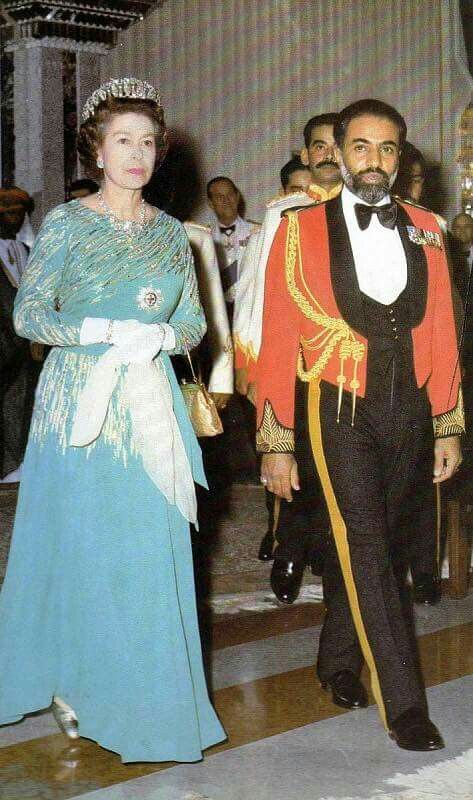

That's when I started asking Qaboos if I could have archaeological permission to carry on searching. Over the 20 years, every now and again, Ginny and I would visit the Oman, including when the Queen did at the invitation of the Sultan. So Qaboos was really happy when eventually, in the early nineties, we founded the Lost City on the Omani side of the border, not the Saudi side!

Sarika Breeze Yes, very good for Oman!

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Yes, good for tourism and so on.

Sarika Breeze And it took you, I believe, eight expeditions before you found it?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Unfortunately, it did, yes.

Sarika Breeze We'll talk more about that in a moment, but first I'll read an excerpt of your book Atlantis of the Sands:

Nashran smiled, and scratched at the sand with his camel stick. ‘Some say the finest city in all Arabia was Ubar, built like Paradise with pillars fashioned from gold. Allah destroyed the place and no man has been there for a thousand years. Ubar is not on the coast but over there’ – he pointed his stick north towards the distant Qara mountains and west towards the Yemen – ‘in the Sands beyond the Wadi Mitan.’

‘Will you take me there, Nashran?’ I asked.

‘Insha’allah,’ was his reply: ‘God willing.’

Many explorers and expeditioners before you, including T E Lawrence and Bertram Thomas, had been interested in finding this Atlantis of the Sands. So how did you manage to find it?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Some of them had found tracks, which gave you directions. If you followed that direction on a map, the way the tracks were going, they could be misleading. Nashran said to me ‘the best way you're ever going to find it is by realising that it would have to have been as far north from Dhofar into the Sands, because they would load the camels with water for 800 or 900 miles. They would therefore want the water to be as far north as it could be’.

All the known wells, to a local taste different – the water. So we would go looking at wells with Nashran or Bedu and we found that the most northerly water of all was at a place called Shisr. In the old days, before I started looking for it, I had used Shisr as a base for my Land Rovers because there was an old Said bin Taimur fortress right out in the sand dunes, and that was the most northerly place for my Land Rovers to get water the early days, in about ‘68. So I knew about Shisr and we used it as our base to go right into the dunes west to north when we were looking for the Lost City.

Sarika Breeze And what made you so determined to search for it when it was potentially legendary and for millennia no one had been able to find it? What made you so certain it existed and that you could be the one to find it?

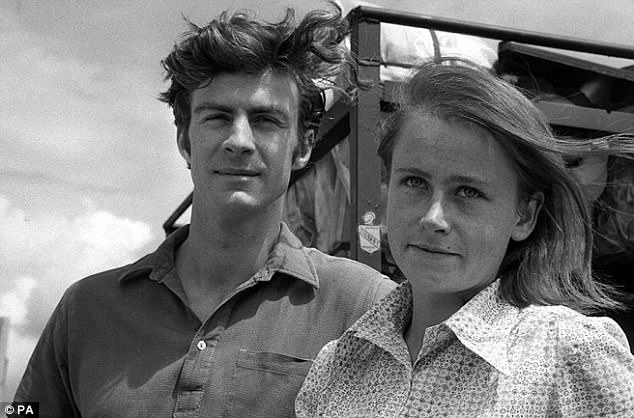

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Well, many reasons which I give in the book Atlantis of the Sands. That would be better than my memory because I would have written it at the time. I know one reason was because of my wife, Ginny, who by then had a good knowledge of Arabic and she had become very, very keen on finding the Lost City.

Sarika Breeze So most of what you had heard about it was from local Omanis rather than reading what other people had written about it?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes That's true because there wasn't very much that they had written about it.

Sarika Breeze Yes, I guess they hadn't found it yet! So, your search for the Lost City in the Empty Quarter was certainly not easy nor quick. It took you eight attempts before the final expedition that uncovered Ubar. How did you motivate yourself to keep coming back between your other expeditions?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Yeah, I mean, at that time we were deeply into Polar record breaking and so we had to get sponsorship for everything we did. Ginny and I didn't have any income. We couldn't pay anybody anything. Everything had to be sponsored. One expedition, the first journey around Earth vertically without flying took Ginny and me seven years of work unpaid to get 1900 sponsors. The Ubar expedition had to slot in between the polar trials and this that and the other.

Sarika Breeze And at what moment did you realise that you had found it?

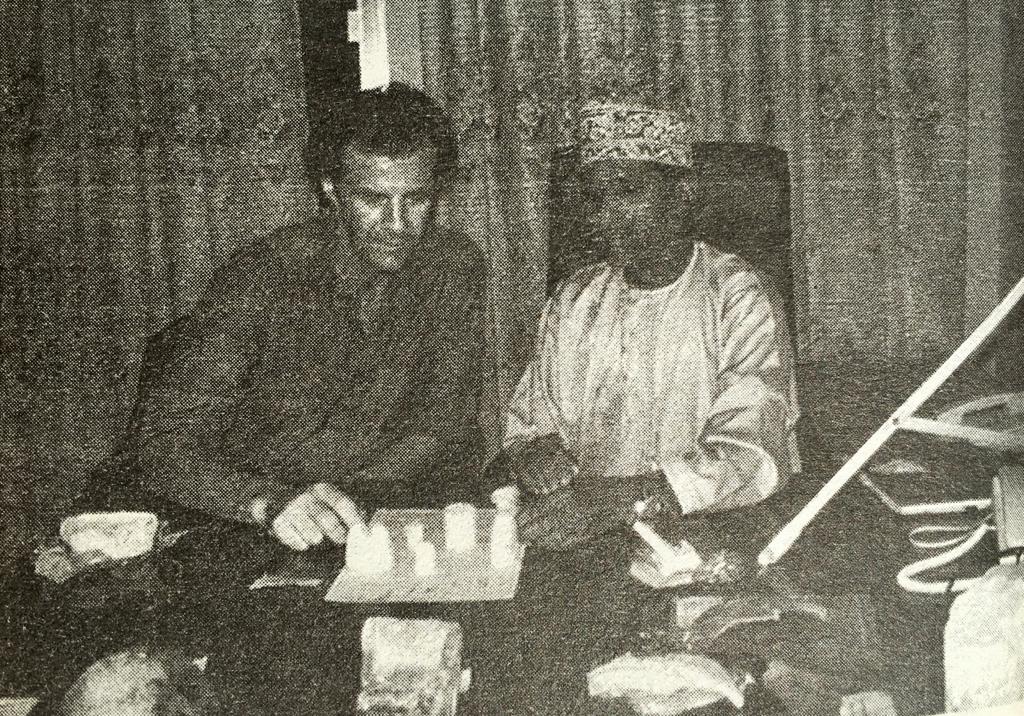

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Well, by then we were using the number one Middle Eastern archaeologist, Dr. Juris Zarins, from Missouri State University. Basically, wherever we went that year, the year we found it, we took with us an American film team. The name of the film they were going to make was called the Search for the Lost City, because they knew that we tried very often and hadn't found it. To call it “the search” meant they could do lots and lots of filming where the Sultan wouldn't normally allow anyone to film.

One day we were in Shisr, the base camp, and Ginny and I in the heat were sitting on one side of a boulder. We heard two people talking just round the other side. Ginny, who’s got very good hearing, put a finger to my lips to hush us up where we were sitting in the shade so she could listen.

You probably won’t remember, but in the old days in Russia, tourists had people called ‘ministry of tourism’ attached to them who were listening to them. Well, in Oman, people who were doing special, allowed things like this, Qaboos allowing us to do it was great, and to have the film team was great, but the ministry of tourism people – two of them – were just around the corner of the boulder and not knowing that we were listening. Basically, what they said was ‘look, nearly two months now, we've been with these Land Drovers. You've got the archaeological lot and the film lot. They're filming everywhere all the time and obviously loving what they're getting, but there's no digging there! They never dig!’ And that was because we’d found nothing. I knew and Ginny knew that these two guys would report to the minister of heritage who would report to the Sultan, who would remove us.

So I rushed off to Juris Zarins and said ‘Juris, you’ve got to dig immediately! Dig! Dig! Dig!’ and he said ‘well, there’s nothing to dig for here. And his team of diggers, about five of them, were from Missouri University, and they thought ‘Juris must've gone mad, making us dig here, because there are no clues!’ The reason Shisr was there, so far into the sand, was because a meteor had struck it there. That's why the Sultan had chosen that for his old fortress. And that had opened up water, deep, deep, deep – you had to go down on a ladder. There was some rubble near the meteorite site, but Juris said ‘no, that was some French archaeologist who was allowed briefly to dig there, but it's a different period to what we're looking for’.

But within two days Juris had found fascinating stuff at the base camp. We used to go hundreds of miles over all that period to look, and we were sitting on it! When we found it, I reported to Qaboos in his palace up North and he was over the moon.

Sarika Breeze And he confirmed that what you were looking for was what you had found as well, didn’t he?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Absolutely. Well, it’s by elimination. There was nowhere else that far north into the Sands anywhere. If there had been one on the Saudi side, it would be found by now.

Sarika Breeze So, how did you come up with the idea of incorporating your adventures in Oman, Canada and Norway into a rum?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes I had had no connection with alcohol previously, but Richard Fitzmaurice, who is the architect of the Ran’s Rum project, met the doctor in charge of the distilleries. He pointed out, which I didn't know, the ingredients of rum. I did know that all my polar expeditions were to try to break records and that a hundred years or so before, Scott and Shackleton tried to beat our main rivals in the world: the Norwegians. We would try to break the records which our predecessors had failed to do, meaning Shackleton's attempt to do the first crossing of Antarctica, which is bigger than America. And we were doing those very same things and that the British attempts at the polar records had all been organised and planned by the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy is synonymous with rum. So that being the case and the fact that Shackleton’s ship sunk, that's why they never managed to cross, and where the ship sunk is where our expedition in the early nineties went.

So we tried to complete the entire continental crossing that he planned from A to B. We were nearly dead at the finish. The team that we took – myself and Mike Stroud – we proved that it could be done by human beings. We did not have dogs to help. Shackleton’s plan, if he hadn’t sunk the ship, would have been with dogs as well. That made it even more likely that his plan, if he hadn't had the bad luck of sinking, would have succeeded. But his critics ever since (none of whom have ever been to the Antarctic by the way) say ‘no, no, he would have died. Definitely’. As it was, after the ship sunk, he became famous for amazing survival, but he’s been criticised ever since. People say that the plan was such that it couldn't have succeeded, people would have starved, et cetera. Well, our expedition eventually proved that no, it could have succeeded.

So Royal Navy and their rum was the basis of Richard Fitzmaurice's plan with the distillery. I didn't know that wood was something which could really sharpen up different tastes of rum.

Sarika Breeze So as soon as you found that out, did you think ‘right, Norway, Canada, Oman, these are the woods I’m using‘?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Yeah. Richard said ‘what woods have you had anything to do with?’

I said ‘well, my expeditions in Antarctic and the Arctic don’t have any trees at all, but my very first expedition, Norway, doing the first descent of the famous glacier, Jostedalsbreen. Then there was Oman which we've been talking about. The Canadian one was because of the National Geographic. We repeated the 50-year-old Nile expedition that we did while on leave from the Sultan’s Army. Last year we went all the way up the Nile, into the pyramids and everything for the National Geographic. And they are planning, this September if COVID allows, to do a 50 year repeat of that one, the British Colombian first water training, down nine rough rivers, from the northern border of Canada to Vancouver, Canada’s southern border with the United States. And on that one, we passed through amazing forests.

Sarika Breeze How do you view the future of exploration and expeditioning? Do you think it's changed significantly in your time, especially in the globalised world we live in now?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes In August, COVID allowing, some of our team will go back to see whether a particular polar expedition, part of that journey of three years around the world, has changed. It involves a small two-man boat with no cover – the very first 3000 miles open boat journey through the Northwest passage. And that, with support from Universal and Netflix, is what we will be doing in August if there are no lockdowns applicable then.

That will tell, in an amazing way, whether the ice, which had just begun to become water and ice when we did it with difficulty back in ‘81, and that expedition, we would be planning to repeat to see how the ice has changed in the Northwest passage.

Sarika Breeze I assume you're anticipating that things will have changed quite a lot?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes The satellite photography is their only way of knowing and that's changing the whole time. Don't forget that it’s not ice and it’s not water, but in between ice (which you can travel over, as we got good at doing and we got good at knowing when it's too thin and will break) and water (which you can go straight through, of course). But the sludge, called shuga, is the dangerous bit, which is neither water nor ice and doesn't show up necessarily on a satellite as being one or the other. So, you can't know for sure what it's going to be like.

Sarika Breeze I'd class myself as an adventurer and an aspiring expedition leader and something I've always admired is your creativity and determination. You are constantly finding untrodden paths. Can you tell me a bit about how you came up with some of these ideas, such as your journey up the Nile in a hovercraft?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes I think that we knew that no tourist, because of the war with Israel, was being allowed up the Nile. However a guy on our team, an army guy, said ‘look, the ministry of agriculture in Egypt, with their big cotton crop industry, they would find a thing called a hovercraft (which had just being pioneered in the UK) could do it much more cheaply, the spraying cotton crops over swamps, because it could move from water to land and land to water’. It was adapted to spray and was much cheaper than aircraft. So instead of just using Land Rovers along the side of the river, why not take hovercrafts. Then when you get to places like Cairo and Khartoum, the agricultural people will be fascinated. And the hovercraft people in Peterborough realised that they could sell the two-seater pioneer hovercraft that they made. So we got onto that.

Sarika Breeze Do you feel that your time in Oman was a formative part of the rest of your life? Did it shape expeditions afterwards?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes The time in Oman fighting the greatly superior, numerically, people in their own country did. I knew a couple of my predecessors who'd been killed. I got to learn exactly what they'd done wrong and realised that you shouldn't approach the mountains from the semi-safety of the desert by day. You should wait till after nightfall and park your vehicles 20 miles away from the mountains, forced march by night, climb right up into the mountains by night, lay your ambush by night and get out by night. As the SAS had taught. So even though I got thrown out of them, as I told you, I had learned lessons, which most of the opposition in Oman just hadn’t learnt at that time. And that was very helpful to my time in Oman. But, carrying expeditions from Oman into polar records, from hot to cold, didn't really teach you much. However, each time you do something, you're learning a bit more about selection of other people.

Sarika Breeze You’ve done expeditions and extreme cold, like Everest and Antarctica, and extreme heat, including the Marathon des Sables and trekking through the Sahara on your trans-globe expedition. Are there different ways that you mentally and physically prepare yourself for expeditions in cold and in heat?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes No, if you're under great pressure mentally and physically, it doesn't matter whether it's the cold or the heat, you've still got the same basic element of a wimpish voice coming into your head unbidden, saying ‘I've got to stop. This is too much’. You didn't ask for that thought but it’s there and it's having a bad effect on your determination and before an expedition, the person in charge wants to choose people who can beat the argument going on in their head and to have some basis for doing so. Very often we found people with religious faith – or faith that's not even religious – have got better able at doing that sort of thing.

From my own point of view, I was brought up in South Africa with a faith called Anglican, which I’ve still got, but it wasn't strong enough in extreme cold to deal with gangrene, frostbite, all that sort of stuff, possible amputations. So I developed my own way of fighting that nasty voice saying ‘you’ve got to stop’, by imagining the two people I most respect: my dad and my granddad. I never met them because they were dead but my mum told me about them and I reckon that they're watching me on these expeditions and I therefore don't want to shame them by being the first to give up. But you never do an expedition if you're sensible by yourself. So what you're hoping the whole time is that the other people or the other person will give up first!

Sarika Breeze And have you ever been the one to drop out first?

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Probably… certainly when it's a solo.

Sarika Breeze It's hard to wait for someone else to, in those situations!

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Yes, and you’ve got no one to hate. It helps, I think, having someone else to hate.

Sarika Breeze Yes. I'm impressed that you've managed to keep the same expedition partners through multiple expeditions because I imagine after three years of the most trying conditions it’s easy to turn against each other.

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Well, when Charlie died 30 years ago, since then, my main colleague has been the same bloke. Each time we hate each other and you’re trekking and the one with the gun is thinking ‘I'll shoot the other one’. But Dr Mike Straud has been a brilliant colleague for 30 years or so.

Sarika Breeze I suppose when you're part of the only group of people that have ever done a certain challenge, you've got a kinship with them that you don't share with anyone else. So despite how much you must hate them in the worst times, you've always got something you've been through together.

Sir Ranulph Fiennes That's a good summary. I agree.

Sarika Breeze Thank you very much for speaking with me today. It's been fantastic talking to you and I've certainly learned a vast amount about Oman and the expeditions you've been on.

For those wondering, Sir Ranulph Fiennes’ Great British Rum is available to order online, as are the many books he’s written. The two most focused on Oman are Where Soldiers Fear to Tread and Atlantis of the Sands.